book by Tobias Wolff*

annotation by Lee Stoops

The young Tobias Wolff—who, in his youth, went by Jack —and his mother Rosemary are driving across the country from Florida to Utah. Rosemary is fleeing an abusive relationship and she hopes that in Utah, she and her son will be able to strike it rich in the uranium boom. The idea of identity and performance will become one of the book’s most prominent themes as it continues to unfold. Here, the young Toby experiments for the first time with making a change to his identity and adopting a persona; he wants to become the archetype of a “Western” boy, and feels he must change parts of himself in order to successfully strike this new “pose.”.

“…because this is a book of memory, and memory has its own story to tell.

But I have done my best to make it tell a truthful story.”~ Tobias Wolff, This Boy’s Life

This Boy’s Life is just that: a boy’s life. Granted, it’s the story of a broken home, a sympathetic and easily-misled mother, and a rebellious and misdirected adolescent, but it’s still just the story of one boy growing up. Wolff pulls together the story of his childhood in a memoir that charms without being charming. He writes honestly and plainly about his youth – a time of making poor choices and learning from very few of them. There is nothing salacious in the pages. It’s not the fantasy life of a fortune’s heir; it’s not the sex-addled tale of a young stud looking for himself in the arms of faceless lovers; it’s not the adventures of a boy dragged to Africa or Mongolia or any other foreign land, forced to adopt foreign ways or be shunned and humiliated. This is the story of a lonely American boy growing up in lower-working class, mid-20th century, rural Washington State. This is a common story. But it’s told so well.

Wolff’s memoir opens with a truck crash and a death. It’s not him, or his single mother, or even anyone he knows. It’s happenstance. His mother’s car has overheated, and the two of them are stranded on a mountain road, running from a dissolved past into an unknown – and terribly uncertain – future, about to witness a semi-truck barrel past. “We stared after it. ‘Oh, Toby,’ my mother said, ‘he’s lost his brakes’” (3). This line of dialog, the only dialog in the opening paragraphs, gives the reader six words spoken by Wolff’s mother; six careful, manipulative, fully-toned words. They give Wolff’s mother away. She’s helpless and aware of her helplessness. In the following lines, Wolff describes seeing the wreck, understanding what happened to the driver, and how his mother spends the rest of the afternoon comforting herself by trying to comfort him. Of course, also by this time, the reader knows that Wolff doesn’t need the comfort but is happy to take advantage of the situation and leaves Grand Junction with toys. In those few short opening paragraphs, the reader knows Wolff’s mother, knows Wolff, and knows their plight. And this is Wolff’s tactic throughout the narrative. He tells his story; tells it scrubbed of emotion, excess language, or many sensory details. Yet, the story evokes nothing but these things. It’s startling just how much is unsaid yet never misunderstood.

“Dwight [step-father] stayed in the utility room for some time. After a spell of silence I heard him rummaging around. Then he said, ‘Come on, Champ.’ My mother and I were reading in the living room. We looked at each other. I went to the window and watched Dwight walking into the dusk, Champion sniffing the ground ahead of him. Dwight was carrying the 30/30. He let Champion into the car and drove away, upriver.

Dwight was only gone for a little while. I knew he hadn’t buried Champion, because he came back so soon and because we didn’t own a shovel” (178).

A master of the transition, Wolff manages to move from story into story without announcement or disconnect. He uses details throughout the narrative to lead the reader in a natural, thoughtful way, and then trusts the reader to make the shift with him. The transitions are never leaps but are always meticulously developed. Early in the story, Wolff talks about a .22 rifle Roy (a man he and his mother lived with at the time) had given him. He describes being alone in the apartment day after day, having agreed to never touch the firearm without his mother or Roy to supervise. Of course he touches it. Touching evolves into dressing in a camouflage coat and shouldering the unloaded weapon, marching like a shoulder. Soon, the young boy Wolff is acting the sniper; using the back of a couch and aiming at people passing by.

“…I followed people in my sights as they walked or drove along the street. At first I made shooting sounds – kyoo! kyoo! Then I started cocking the hammer and letting it snap down.

Roy stored his ammunition in a metal box he kept hidden in the closet” (25).

The transition is a tricky element, and Wolff succeeds every time because he trusts the reader to move with him without writing the reasons for the movement – he’s already set the story in motion, and, though it could go a number of ways, the reader expects it.

This Boy's Life Netflix

Wolff uses details freely, but very seldom describes things in vivid detail. When describing Veronica (an older girl he met while in the company of his rowdy high school buddies), he uses one sentence, but the reader can see her clearly: “She still had the pert nose and wide blue eyes of the lesser Homecoming royalty she’d once been, but her face was going splotchy and loose from drink” (186). Veronica is in the picture because of sex, not that there is a sex scene. Wolff’s buddies sleep around and try to fix him up with girls (they’re flabbergasted that he’s a virgin), but he keeps backing out. On the page after describing Veronica, Wolff describes his ideal, in vivid detail and interior perspective:

“I wanted to be with the girl I loved.

This was not going to happen, because the girl I loved never knew I loved her. I kept my feelings secret because I believed she would find them laughable, even insulting. Her name was Rhea Clark. Rhea moved to Concrete [Washington] from North Carolina halfway through her junior year, when I was a freshman. She had flaxen hair that hung to her waist, calm brown eyes, golden skin that glowed like a jar of honey. Her mouth was full, almost loose, she wore tight skirts that showed the flex and roll of her hips as she walked, clinging pastel sweaters whose sleeves she pushed up to her elbows, revealing a heartbreaking slice of creamy inner arm” (187).

This mixing of descriptive styles does two things: 1) it gives the reader freedom to move smoothly through the narrative, relying on his/her own imagination for clarity and sense and 2) creates more power in the instances of fuller reveal.

Another blending technique Wolff uses is that of perspective. At times, the voice of the first-person narrator will move seamlessly between his boyhood experience and perspective, stirring in his grown perspective. One of the greatest examples in the book is his fight with Arthur and Arthur’s dog Pepper. Wolff tells of calling Arthur a “sissy” and of Arthur losing it. They exchange blows and eventually roll into the mud. It’s all very much his boyhood experience.

“Pepper followed me in my descent, yapping and lunging. There hadn’t been a moment since the fight began when Pepper wasn’t worrying me in some way, if only to bark and bounce around me, and finally it was this more than anything else that made me lose heart. It wounded my spirit to have a dog against me. I liked dogs. I liked dogs more than I liked people, and I expected them to like me back” (110).

The Cisco AnyConnect Secure Mobility Client has raised the bar for end users who are looking for a secure network. No matter what operating system you or your workplace uses, Cisco enables highly. Download the Cisco AnyConnect VPN client in the Related Download box in the upper-right of this. Cisco anyconnect download. Launch the Cisco AnyConnect Secure Mobility Client client. If you don't see Cisco AnyConnect Secure Mobility Client in the list of programs, navigate to Cisco Cisco AnyConnect Secure Mobility Client. When prompted for a VPN, enter su-vpn.stanford.edu and then click Connect. Enter the following information and then click OK.

The line “It wounded my spirit to have a dog against me” is a grown person’s perspective and words, and yet, it fits exactly as it should in the boy’s story.

Of course, Wolff is not without his faults as a writer. There are a number of head-scratching instances in the narrative – places that his story tangents to reflecting upon his grown life and family. The reflections are meaningful and well-written, but inconsistent, infrequent, and, every time, unexpected. Unexpected turns in narrative are interesting, but unexpected and out-of-place monologue-type reflections are distracting. On page 120, Wolff writes about life with his step-siblings, specifically sharing a room with Skipper and how disappointed he is by the way Skipper treats him. Naturally, Wolff shifts to wondering what life would have been like had he stayed with his father. And then, out of the blue (on pages 121-122), he writes about the future – visiting family later in life after Vietnam and being in the Army, about the birth of his own children, about everything that happens well after This Boy’s Life is over. It happens again on pages 232-233: he writes about Dwight’s voice being ever-present in his head and own voice, even as an adult, even as a father. “I hear his voice in my own when I speak to my children in anger. They hear it too, and look at me in surprise. My youngest once said, ‘Don’t you love me anymore’” (232-233)? The intention is clear, and the meaning is powerful, but the mention of his future life is surprising and unexpected; distracting.

Wolff’s power is a blend of prose and authenticity. As a reader, I found it hard to put the book down. As a writer, it was impossible for me to stop reading and noting his careful, direct, and artful style. Anyone can learn from someone else’s honesty, but it takes a truly bold story-teller to be that someone else – especially that someone else who can piece it all together so clearly and entertainingly.

*Page references are from Wolff, Tobias. This Boy’s Life. New York: Grove Press, 1989. Print.

| This Boy's Life | |

|---|---|

| Directed by | Michael Caton-Jones |

| Produced by | Fitch Cady Art Linson |

| Screenplay by | Robert Getchell |

| Based on | This Boy's Life by Tobias Wolff |

| Starring | |

| Music by | Carter Burwell |

| Cinematography | David Watkin |

| Edited by | Jim Clark |

| Distributed by | Warner Bros. |

| |

| 115 minutes | |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Box office | $4 million[1] |

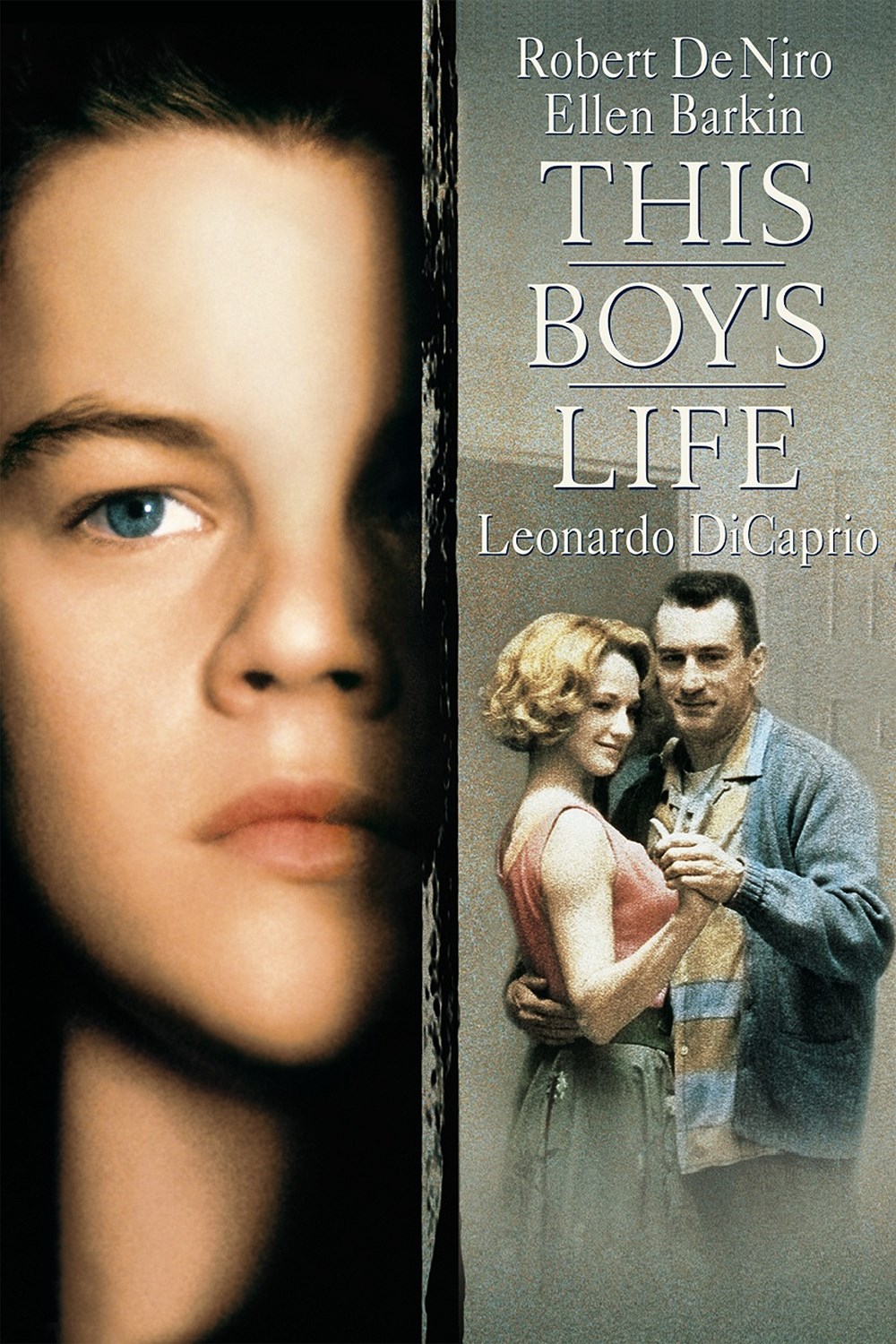

This Boy's Life is a 1993 American biographicalcoming-of-agedrama film based on the memoir of the same name by author Tobias Wolff. It was directed by Michael Caton-Jones and stars Leonardo DiCaprio as Tobias Wolff, Robert De Niro as Toby's stepfather Dwight Hansen, and Ellen Barkin as Toby's mother, Caroline. The film also features Chris Cooper, Carla Gugino, Eliza Dushku and Tobey Maguire.

Plot[edit]

In the 1950s, nomadic and flaky Caroline Wolff wants to settle down and find a decent man to provide a better home for herself and her son, Tobias 'Toby' Wolff. She moves to Seattle, Washington and meets Dwight Hansen, a man who seemingly meets her goals. However, Dwight's true personality is soon revealed as being emotionally, verbally, and physically abusive to Toby while Caroline is away for a few weeks.

The marriage proceeds, and Caroline and Toby move into Dwight's home in Concrete, a small town near the north Cascades Mountains. Dwight's domineering personality is soon apparent, but Caroline remains with him, enduring several years of a dysfunctional relationship. During this time, Toby befriends a classmate named Arthur Gayle, a misfit at school and ambiguously gay. Toby wants to leave Concrete and live with his older brother, Gregory, (who lives on the East Coast with their father). Toby plans to apply for scholarships at East Coast prep schools by submitting falsified school records. Meanwhile, Arthur and Toby's friendship becomes strained when Arthur accuses Toby of behaving more like Dwight. Arthur helps Toby to falsify his grade records. After numerous rejections, Toby is accepted by The Hill School in Pottstown, Pennsylvania near Philadelphia with a full scholarship.

Later, Caroline defends Toby from Dwight during a physically violent argument; they both leave Dwight and the town of Concrete.

(Note: The real Dwight died in 1992. Caroline (Rosemary Wolff) remarried and moved to Florida. Arthur Gayle left Concrete and became a successful businessman in Italy. Dwight's children all married and lived in Seattle. Toby and his brother Geoffrey both became noted writers.)

Cast[edit]

- Leonardo DiCaprio as Tobias 'Toby' Wolff

- Robert De Niro as Dwight Hansen

- Ellen Barkin as Caroline Wolff Hansen

- Jonah Blechman as Arthur Gayle

- Eliza Dushku as Pearl Hansen

- Chris Cooper as Roy

- Carla Gugino as Norma Hansen

- Zack Ansley as Skipper Hansen

- Tracey Ellis as Kathy

- Kathy Kinney as Marian

- Tobey Maguire as Chuck Bolger

- Michael Bacall as Terry Taylor

- Gerrit Graham as Mr. Howard

- Sean Murray as Jimmy Voorhees

- Lee Wilkof as Principal Skippy

- Bill Dow as Vice Principal

- Jen Taylor as Deputy O'Riley (uncredited)

- Deanna Milligan and Morgan Brayton as Silver Sisters

Production[edit]

Largely filmed in the state of Washington, the town of Concrete, Washington (where Tobias Wolff's teen years were spent with his mother and stepfather, Dwight), was transformed to its 1950s appearance for a realistic feel. Many of the town's citizens were used as extras, and all external scenes in Concrete (and some internal scenes, as well) were shot in and around the town, including the former elementary school buildings and the still-active Concrete High School building. Parts of the film were also shot in the La Sal Mountains in Utah.[2]

Release[edit]

Box office[edit]

The film was released in limited release on April 9, 1993, and earned $74,425 that weekend;[3] upon its wide release on April 23, the film opened at #10 at the box office and grossed $1,519,678.[4] The film would end with a domestic gross of $4,104,962.[1]

Critical reception[edit]

The film received mostly positive reviews; review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes gave the film a 76% 'Fresh' rating from 37 critics, with an average rating of 6.4/10. The site's consensus states: 'A harrowing, moving drama about a young boy, his single mother, and his abusive stepfather, This Boy's Life benefits from its terrific cast, and features a breakout performance from a young Leonardo DiCaprio.'[5] On Metacritic, where they give a 'normalized' score, the film has a 60/100.[6]

Home media[edit]

This Boy's Life was released on VHS September 1, 1993 and on DVD May 13, 2003.

Soundtrack[edit]

The soundtrack of This Boy's Life used many songs from the 1950s and early 1960s. The main titles (filmed in Professor Valley, Utah) feature Frank Sinatra's version of 'Let's Get Away from It All' from his 1958 album Come Fly with Me. Toby and his mother sing 'I'm Gonna Wash That Man Right Outa My Hair' from the popular post-war musical South Pacific. However, most of the music reflects Toby's fondness for rock and roll and doo wop, including songs by Eddie Cochran, Frankie Lymon and the Teenagers, and Link Wray. Carter Burwell composed the film's pensive score, which featured New York guitarist Frederic Hand.

Tobias Wolff This Boy's Life

References[edit]

- ^ ab'This Boy's Life (1993)'. Box Office Mojo. Retrieved July 12, 2010.

- ^D'Arc, James V. (2010). When Hollywood came to town: a history of moviemaking in Utah (1st ed.). Layton, Utah: Gibbs Smith. ISBN9781423605874.

- ^This Boy's Life at Box Office Mojo.

- ^This Boy's Life at Box Office Mojo.

- ^This Boy's Life at Rotten Tomatoes

- ^This Boy's Life at Metacritic

External links[edit]

- This Boy's Life at IMDb

- This Boy's Life at Box Office Mojo

- This Boy's Life at Rotten Tomatoes

- This Boy's Life at Metacritic

- This Boy's Life film trailer at YouTube

Tobias Wolff This Boy's Life Interview